Finite-size effects in quantum computations of scattering

This is an informal summary of: The role of boundary conditions in quantum computations of scattering observables. Recently, there has been a strong push worldwide to accelerate the development of quantum technologies and in particular quantum computing. One future application could be real-time simulations of quantum field theories, possibly including quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the mathematical description of the strong nuclear force. The idea of “real time” here is in contrast to the current numerical state of the art, a framework called lattice QCD. Lattice QCD relies on imaginary times (replacing real $t$ with $t = - i \tau$, where $i = \sqrt{-1}$ and $\tau$ is made real so that $t$ is an imaginary number). This is a mathematical trick that makes the calculation work, but it can severely limit the physical predictions one can extract.

One class of observables where this plays an important role is that of scattering amplitudes. Consider, for example, the scattering amplitude describing $$p \pi^- \to n \pi^+ \pi^- .$$ This is naturally a real-time process; at early times a proton and a negative pion are separated and fly toward each other, at intermediate times they collide, and at late times a neutron and a charged pion pair emerge and hit the detector.

So three natural questions arise:

Can we somehow calculate such processes with current methods (i.e. numerical lattice QCD)?

Can we calculate such processes with future quantum computers?

In which cases, and to what extent, will quantum devices provide a significant advantage in extracting this information?

The answer to the first question is a resounding yes! The most useful method so far is to use the finite system size in the numerical calculation (often called the finite volume) as a probe of the interactions. In particular, the finite volume leads to a set of discrete energies, and the values of these energies can be used to determine the scattering amplitude.

The answer to question number two is also yes, but in this case the finite volume can only be seen as an unwanted artifact. This turns out to be a very important issue when answering question number three, and this is the motivation for our work: Compare the extraction of scattering information from imaginary-time calculations (where the finite volume is a useful tool) to the extraction from real-time calculations (where the finite volume becomes an unwanted artifact).

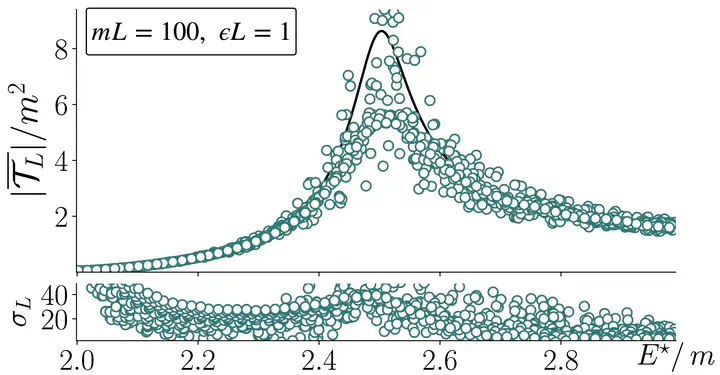

The logic is potentially confusing, as one needs a strategy to predict how the real-time scattering information will be distorted by the finite volume. To do this, we used the same methods as in lattice QCD, but ran them backwards. So instead of using finite-volume energies and matrix elements to predict amplitudes $$E_n(L), \langle n, L \vert \mathcal J \vert m, L \rangle \ \longrightarrow \ \mathcal M_{\pi \pi \to \pi \pi}, \ \mathcal T_{\pi \gamma \to \pi \pi} , $$ we use models of the infinite-volume amplitudes to predict the finite-volume information $$\mathcal M_{\pi \pi \to \pi \pi}, \ \mathcal T_{\pi \gamma \to \pi \pi} \ \longrightarrow \ E_n(L), \langle n, L \vert \mathcal J \vert m, L \rangle , $$ and this, in turn, to predict the finite-volume amplitudes that one could extract in future quantum computers $$ E_n(L), \langle n, L \vert \mathcal J \vert m, L \rangle \to \mathcal M_{\pi \pi \to \pi \pi}(L) .$$ From here we can compare the finite- and infinite-volume versions of $\mathcal M_{\pi \pi \to \pi \pi}$ directly.

The punchline of this article is that finite-volume effects can be so significant that it is not always clear whether real time offers a clear advantage. This is especially true for systems with interesting types of interactions, including short-lived particles (resonances) that form and then immediately decay in the scattering process. The biggest advantage will be for scattering at higher energies and for amplitudes where many particles are involved. Finally, in this article we describe some strategies to reduce the volume effects and illustrate how well they work. This is only the first step towards answering these questions and the work has some clear limitations. So far, we have focused on systems with only one spatial dimension (instead of three) and on scattering amplitudes where only one type of particle is involved. Work is already underway to lift these restrictions and investigate the situation for more complicated systems.